31 August 2011

Joke for the day

Rico says his friend Tex sends along this one:

A man, laid off from work, went into a job center in downtown New York City and saw a card advertising a job as a gynecologist's assistant. Interested, he asked the clerk for details.

The clerk pulled up the file: "The job entails getting the ladies ready for the gynecologist. You have to help them out of their underwear, lay them down, carefully wash their private regions, then apply shaving foam and gently shave off the hair, after which you must rub in soothing oils so they're ready for the gynecologist's examination. The annual salary is $175,000, but you'll have to travel to Burlington, Vermont."

"Good grief, is that where the job is?"

"No, sir, but that's where the end of the line is right now."

Movie review of the day

Rico says it came as an extra from Netflix, and stars a young Alain Delon, but Borsalino & Co. is tedious and very French (though the Art Deco-era sets are spectacular).

Separated at birth

Rico says that would be Bill Sarnoff (top), a friend from our days at Claris, and Charlie Haas (bottom), a friend from Gunn high school.

Quote for the day

Porn isn't bad. Men watching porn is like women watching the Food Network: we're both watching things we can't have.

Whitney Cummings, comedian and star of the eponymous NBC show Whitney.

Swan song for a rat

Rico says that, if he was better at song parodies (and where's Charlie Haas when you need him?), this would become Farewell to Qaddafi...

A nice destination

Matt Gross, the former Frugal Traveler, who writes the Getting Lost series, has a article in The New York Times about a lovely place:

Sing to me of the man, O Muse, that cleverest of men, most favored by the gods, most frustrated by them, too. Sing to me of endlessly lost Odysseus, whose ten-year journey home, from the scorched and blood-stained plains of Troy to the Ionian island of Ithaca, was a decade of disaster. Sing to me of the Cyclops, the Sirens, Calypso and Circe, Scylla and Charybdis, of challenges confronted and conquered, destiny delayed and at long last achieved.

So sing to me, I begged the Muse one Friday evening in May, or, hey, you know what? Just send me an intercity bus: I’ve gotta get out of here.

“Here” was the seaside town of Neapoli, at the southeastern end of the Peloponnesian peninsula of Greece, where nearly two weeks of island-hopping from the Turkish coast across the Aegean Sea had come to a sudden and maddening halt. From Cape Maleas— the last location Odysseus himself recognized before the North Wind drove him into the monster-ridden lands of myth— all I had to do was hop a bus or two to the port of Patras, and from there a ferry could take me, at long last, to Ithaca, the place Odysseus called home.

In Neapoli, however, there were no buses until morning, and I had no choice but to spend the night in this cheerful, if sleepy, seaside town. Even a day or two earlier, I wouldn’t have minded. In fact, for the previous ten days I’d been delighted by the capricious whims of bus and ferry schedules. But I was due to fly home to New York from Athens in two days, and now this delay was unbearable.

As I numbed disappointment with ouzo at a waterfront restaurant, I noticed something unusual on the sidewalk before me: a penny-farthing, one of those nineteenth-century bicycles with an enormous front wheel and tiny rear one. The owner, it turned out, was Jim, a twenty-something hairdresser from Athens who was sitting nearby with his girlfriend, Chara, a schoolteacher. They were a sweet couple, definite hipsters, and I smiled when they asked me, as had practically every Greek I met on my journey, how I’d wound up here. “I’ve come from Troy,” I said, “and I’m trying to get to Ithaca. Like Odysseus: no map, no guidebook, no route, no Internet, no hotel reservations.”

Thus began a tale I’d been telling, and adding to, ever since I’d begun my Odyssey in Turkey outside the city of Çanakkale, where ancient Troy was located and, beginning in the late nineteenth century, unearthed.

But Troy was not where I wanted to linger. It was, for both myself and Odysseus, a starting point. My plan was not to follow the hero’s exact route— it stretched, some say, as far as Gibraltar, and was mythical in any case— but to stumble in his footsteps and try to get a glimpse into his psyche as he tried and failed and tried again to reach Ithaca, a mere 350 miles away as the crow flies, off the west coast of Greece.

Or maybe that’s the wrong way to put it. For Odysseus has no psyche, not in the modern, literary sense. One of the founding works of Western literature may be a travel story about getting lost but, apart from the image of heartbroken Odysseus crying on the shores of Calypso’s island, Homer rarely portrays his hero’s disconnection and desperation.

How does that lostness feel, I wanted to know, especially in Greece, where the lonely spaces between rough and empty islands are balanced by an unmatched reputation for hospitality? So, with eleven days for the journey ( Odysseus took ten years, but my wife is less patient than his Penelope) I left Troy to find out.

Immediately, I encountered uncertainty. Several Greek islands— Limnos, Lesbos, Chios— lie close to Turkey, but no one was sure when, or if, ferries were running. And that was even before Greece’s austerity measures prompted port blockages, transit strikes, and sometimes violent demonstrations in Athens. (The ferries, however, kept running.) The Çanakkale tourism office suggested a three-hour bus south to Ayvalik, where I might find a ferry to Lesbos, and if that didn’t work, I could go farther south, to Izmir, alleged birthplace of Homer himself, and get the ferry to Chios. So, while Odysseus had sailed north with his twelve black ships to raid the lands of the Cicones, I went the other way.

Unlike Odysseus, I got lucky. In Ayvalik, a lovely Turkish town with a jumble of old streets at its center, ferries were leaving for Lesbos.

The two-hour ride was to be a typical one. Inside the ship, whose homey décor had not been updated in a couple of decades, about a hundred families, couples, and groups of friends mostly kept to themselves, snacking on sweets packed for the trip. This was a modest ferry; other, larger ones would have free wi-fi and show reruns of Friends dubbed into Greek. Outside was more exciting: the water flat and sparkling with golden-hour light, small sailboats and fishing skiffs cruising near shore, tiny islands silhouetted by the setting sun.

When the ferry docked in Mytilene, Lesbos’ main town, night had fallen, and I hurried into the nearest travel agency and learned that a ferry to Chios was scheduled for 8:30 in the morning, twelve hours from now. Okay, so, where could I get to from Chios? The travel agent did not know, and his ignorance would prove normal for the islands. People might know which ferries left from the local port, but from other ports? Might as well ask about ferries in Indonesia! This was a challenge. Any embarkation could be a dead end, forcing me to retreat and replan my route. I’d just have to trust Hermes, god of travel, and see what happened.

I would also have to enjoy myself as much as possible, and so I got right down to it in Mytilene, walking through a maze of pedestrian shopping streets until I spotted the Old Market Cafe, which was small, lively, and untouristy. But no sooner had I ordered (mint-spiked meatballs, white beans with dill, tomato-cucumber salad) than I heard a commotion outside. Perhaps two hundred young people were marching through the dark, chanting slogans and handing out flyers decrying police brutality. (I don’t read Greek, but there was a helpful illustration.) It was my first taste of the crisis that has been engulfing Greece since 2008, and I was tempted to follow the marchers and learn more. “But there’s no way to hide the belly’s hungers,” Odysseus once remarked. “What a curse, what mischief it brews in our lives!” So I ate, had a couple beers with off-duty soldiers at a bar, and paid too much for a hotel room.

At dawn I boarded the ferry to Chios. Again, a smooth ride through sun-dappled waters. This time, however, my reading material, The Marriage of Cadmus and Harmony, by Roberto Calasso, caught the attention of an American couple who used to lead Sierra Club trips around Europe. The man— who had been visiting Greece since the 1950s, had converted to Orthodox Christianity, and had taken the name Theofilos— appreciated my endeavor, and urged me to visit Ios, where Homer was supposedly buried. This was precisely the kind of tidbit I’d been hoping for, and I swore I’d try to visit Ios, wherever Ios happened to be.

First, though, Chios. Once again I stepped off the ferry and into the nearest travel agency, where I learned that a ferry for Samos, to the southeast, was leaving the next afternoon, giving me time, at last, to explore a Greek island. But where to go? I explained my quest to the travel agents, who told me that the house where Homer had lived was in the village of Volissos, along with a nice cafe. Volissos was, however, 25 miles away, and, with no public transportation, I’d have to rent a car. Minutes later my little Hyundai was navigating switchbacks up cliffs, cruising an arid, boulder-strewn plateau, descending S-curves to the western shores of Chios, and finally parking at the edge of Volissos, whose dense, haphazard lanes climbed a steep hill crowned by the ruins of a castle built during three hundred years of Genoese imperial rule.

At Pythonas, a simple, spacious cafe across from a church, the owner, Maria Siderias, spoke English with a strangely familiar accent. She was from Astoria, the Greek neighborhood in Queens, she explained, as she poured me good local wine and prepared fava beans with garlic sauce, grilled sausage, and a tomato-cucumber salad. She had lived in New York until she was twenty, she said, but, during a family visit to Volissos nineteen years ago, she realized she didn’t want to leave. New York life was volatile; Volissos, land of her ancestors, would be a new start. By returning, Maria was bucking the trend. Once, she said, three thousand people had lived here, but ever since the Germans came, so many villagers had left for Athens and abroad that the population was now maybe two hundred.

“Germans?” I asked, wondering if she meant European Union bureaucrats, or wealthy Continental property-buyers. “You know, in the war,” she said. Oh, the war. World War Two. Those Germans.

Funnily enough, Maria had never sought out Homer’s house, but encouraged me to search atop the village hill. All I found, though, were meticulously restored vacation homes and Stella Tsakiri, an artsy Athenian transplant spattered with paint from renovating her rental properties. “It’s rumors,” she said of Homer’s residence. Rather, she said, Volissos had been home to a clan that claimed to have descended from Homer. And, even if the poet had lived in Volissos, she added, the village itself had moved around, ascending from its original seaside location in the Genoese era.

Rumors, though, were enough for me, and when I returned that night to the Pythonas Cafe (after stashing my things in the free apartment Stella had offered), I listened raptly to Thomas Kanaris, an aging saddlemaker whom Stella called “the soul of the village”, tell a different story. According to him, Homer’s house had been “rebuilt and rebuilt and rebuilt” so many times it was no longer the same structure.

The next morning I drove back to the port of Chios and boarded the ferry for Samos. “What are they here?” curious Odysseus would ask of each new island. “Violent, savage, lawless? Or friendly to strangers, god-fearing men?” On Chios, I knew the answer. Samos, however, was not Chios. First of all, where Chios was rocky, Samos was verdant, a fact I appreciated as I cruised its milder coast in another rented car. But finding a place to stop— welcoming but not touristy, isolated but not abandoned— was difficult. None of the stunning, cliff-perched hill towns I checked out fit the bill. Tourists there were like olives: ubiquitous, entrenched, almost beneath notice.

Oh, but the driving! I kept on west, rounding the coast until the sun melted into the shadows of the hills and the roiling, wine-dark sea. The momentum, both physical and psychological, carried me through the evening, blotting out the throbs of music from a too-close disco as I slept in the city of Karlovassi.

Over all, I didn’t feel let down. On my way back to port the next morning, I stopped for an espresso at the North Star Cafe in the beachside village of Agios Konstantinos, and had a nice chat with Little Jim, an old Greek who had worked much of his life in Australia and had the black-and-white photos to show it. Our conversation ranged from his father (the first villager killed by Nazis) to the troubles engulfing Greece (austerity, unemployment, ethnic strife) to his mother, who had, at the age of one hundred, returned to die here in the village of her birth. Little Jim’s eyes, light brown but rimmed blue-green, were tearing up. Like Odysseus of Ithaca and Maria of Volissos, he had, in troubled times, found refuge in his native land.

The lesson of Samos— no expectations— was good preparation for Mykonos, which I knew by reputation as the party island of the Cyclades, a place of beaches, booze, bikinis, and stark beauty (treeless cliffs, boxy whitewashed homes, blue-painted shutters). Not where people muse over classical literature. But Mykonos is also a ferry hub. You can get almost anywhere from there, and it was time for serious decisions about how to reach Ithaca. Some 150 miles to the south, I knew, lay Crete, Greece’s largest island, where I guessed there might be a ferry to the island of Kythira, roughly fifteen miles off the mainland.

This was a gamble. I could get to Crete and discover that there was no westbound ferry and have to backtrack. But I’d been lucky so far, right? So, after a day on Mykonos, where I went swimming, bought handmade sandals and watched an old woman selling vegetables from her donkey, I boarded a high-speed catamaran bound for Ios.

Yes, Ios, site of Homer’s alleged tomb, just happened to be on the way to Crete. I couldn’t skip it. And once again, the gods were with me. A portside travel agency booked me into the high-end, modern Liostasi Hotel, a mere forty euros a night (about $56, at $1.40 to the euro). Spiros, a Liostasi clerk who, with his beard, tortoiseshell glasses and ironic mannerisms could have been my neighbor in Brooklyn, told me where to grab dinner. And when, with zero effort, I located his recommendation, Katogi, in the labyrinth of Ios’ main village, I bonded with the bartender, Anastasia, who wholeheartedly endorsed my plan to pass through Kythira, her favorite island in all of Greece.

In the morning, with hours to go before the ferry to Crete, I drove out to Homer’s tomb, which lay, appropriately, at the very end of a small highway. A path led through knee-high bushes of wildflowers to a crest above the sea, and a half-collapsed pile of marble blocks. Could this really be Homer’s resting place? Sure, I thought, why not? I plucked a thatch of fragrant wild thyme and returned to the port.

Arriving after dark in Heraklion, Crete’s capital, I had another run-in with Greek provincialism. No one knew when or whether ferries ran to Kythira; one port clerk suggested I wait till morning and call the ferry company. Wait 'til morning? Spluttering with rage at these insular islanders who didn’t even know how to get around their own country, I stormed out of the port and into the bus station, where I drank a calming beer and boarded a late-night shuttle west. The next day I found a ferry to Kythira, leaving in 24 hours. I’d have to wait till morning again.

So again, a rental car. Then the untamed mountains of Crete: goats on the winding road, azure waters below, olive groves silvering the slopes. Again, an honest taverna lunch: lamb stew, sour wine, a tomato-cucumber salad. I use “again” this way not as a complaint, but as an indication of the lush rhythm my life had fallen into. There was a regularity to the joy of discovering these new places, each so similar, none identical.

Below the village of Kampos, I spent hours descending the local gorge, following paths that vanished and reappeared and vanished again, down to a deserted, pristine beach where I felt like the last man alive, or like Odysseus, cast ashore in unknown lands.

Such episodes provoked ambivalence, too. Because as much as I loved them, I also needed to keep moving toward Ithaca. On Kythira, that feeling grew only more acute, amplified by the island’s rugged vastness (3,300 people live on 116 square miles), by my inability to rent a car (for the first time, I was asked to show an international driver’s license) and by the crack of thunder and a cold downpour of rain, which hit just after I’d hitchhiked to the island’s biggest town and settled under a taverna’s awning for lunch. Of course, the rain eventually eased and I found another, kinder rental-car outfit, and I drove back roads through luxuriously arcing hills to reach teeny-tiny Avlemonas, a village recommended by Anastasia of Ios, where the sounds of cool jazz and blues lured me to the waterside Mirodia Kalokairiou Cafe. For a while I sat drinking Belgian beer and watching clouds rise over a ridge with the goateed owner, Stavros, and his employee, Stefanos, a recent cooking-school graduate. “That one looks like a man,” said Stefanos. Stavros agreed: “Like the god Hermes.”

When Odysseus lost his way after Kythira, he landed ten days later in the land of the Lotus-eaters. I was there already. The beer, the comradeship, the casual mythological references, the braised goat at Stefanos’ family’s restaurant, the dramatic gorges and homey cafes and earthquake-ravaged churches; why move on? If Ithaca represents sought-after home, Stavros said: “Kythira is the opposite of that. It’s the paradise you can never find.”

And yet I had to move on. So, first to Neapoli, then to Corinth and Patras, 230 miles north and west, then to Kyllini, another thirty miles southwest, then by ferry to the island of to Kefalonia, and from there to Ithaca.

After eleven days and untold miles at sea, the island appeared, wreathed in morning mist, mountains lined up, hump to hump, like sleeping green camels. The port stayed hidden from view until the ferry’s final approach. Along with several dozen well-dressed Spanish tourists, I stepped onto the land of King Odysseus.

And then nothing. With five hours before the ferry back to Kefalonia, where I’d get a bus to Athens, I took a taxi from the port to Vathy, Ithaca’s capital, whose stately buildings edged a shallow bay. There I had a coffee at one cafe, and another at another. I visited an archaeological museum with a collection of coins, pottery, and statuettes dug up all over the island. One was a brass figurine, about an inch high, of Odysseus, his chin jutting, his eyes facing the heavens.

All around town, wall maps pinpointed the far-flung locations of Homeric sites such as Eumaeus’ pigsty, the nymph’s cave, and Odysseus’ palace. Other posters advertised Island Walks, a tour company offering Odyssey-themed strolls around Ithaca. But I ignored them. For Odysseus, Ithaca meant an end to his wanderings, and I wanted to stop moving too, to see how stillness felt.

It felt unnatural. And I knew well why: Odysseus’ Ithaca was not my Ithaca. Mine lay elsewhere, back in Brooklyn, or perhaps beyond. And now it was time to go.

Before returning to the port, though, I called up Ester van Zuylen, the Dutchwoman who runs Island Walks (her number was on the posters), and told her about my journey. By chance, she had to drop a friend at the port, so we met there to chat and watch schools of fish swim in the crystalline sea.

For a while she talked about the challenges of getting local government support for her work— clearing the paths, promoting the tours— and in general how difficult it was to capitalize on the island’s sole claim to fame. This was a place, after all, where Penelope remained a popular women’s name and, although no men were named Odysseus, Homer was quite common.

Minutes later, a Mazda pulled up. "Oh, here’s Homer now,” Ester said. Homer’s arrival signaled my departure, and I took my last looks at the waters I hadn’t swum and the hills I hadn’t climbed. A day earlier, a friend had emailed me Constantine Cavafy’s poem Ithaca, and a few of its lines stuck in my head: Ithaca gave you the marvelous journey. Without her you wouldn’t have set out. She has nothing left to give you now. As I boarded the ferry, there was nothing else I wanted.

IF YOU GO, HOW TO GET AROUNDRico says it's on his life-list, awaiting only a lottery win...

Since there are no definitive online ferry maps for the Greek islands, if you want to plan ahead the best resource is Ferries.gr, which also lets you book tickets no fewer than four days in advance. Otherwise, you can buy tickets at kiosks and travel agencies in the islands.

Few islands have public transportation, so be prepared to rent cars. All port towns I visited had at least one rental-car outfit. Prices for a manual-transmission compact are twenty to thirty euros a day ($28 to $42, at $1.40 to the euro), including insurance. Some companies insist you have an international driving permit, so get one from AAA for fifteen dollars. Scooters, too, require a different driving license. For information on how strikes and protests may affect travel in Greece, visit livinginGreece.gr/strikes.

WHERE TO EAT AND DRINK

Chios: Pythonas Taverna, Volissos, (30-22740) 21134 and Kechrimpari, 7 Agios Anargiros, Chios Town, (30-69) 4242-5459, which served me the best meal, seven courses plus a bottle of ouzo, for just twenty euros.

Ios: Katogi, main village, (30-69) 7659-8659.

Crete: Sunset, Kampos, (30-28220) 41128.

Kythira: Mirodia Kalokairiou, Avlemonas, (30-69) 7708-1023 and Skandia, Paleopoli, (30-27360) 33700.

WHERE TO SLEEP

Since I couldn’t plan ahead, the places I slept were hit-or-miss. Here are the hits:

Ayvalik, Turkey: Antikhan Boutique Hotel, 216 Sakarya Caddesi; (90-266) 312-4610; antikhanpansiyon.com; rooms from forty Turkish lira, or about $26.

Chios: Vacation apartments in Volissos can be booked through Stella Tsakiri’s Volissos Travel (30-22740) 21421; volissostravel.gr; from 58 euros a day, including rental car.

Mykonos: Hotel Sourmeli Garden, (30-22890) 28255; sourmeligardencom; doubles from 35 euros.

Ios: Liostasi Ios Hotel & Spa, (30-22860) 92140; liostasi.gr; doubles from 115 euros.

Kythira: Sotiris, Avlemonas, (30-27360) 33722; rooms from 30 euros.

Yeah, but not fired

Charlie Savage has a followup article in The New York Times about the BATFE:

The Obama administration has replaced two top Justice Department officials associated with an ill-fated investigation into a gun-trafficking network in Arizona that has been at the center of a political conflagration. Attorney General Eric H. Holder Jr. announced the resignation of the United States attorney in Phoenix, Dennis K. Burke, and the reassignment of the acting director of the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives, Kenneth E. Melson.Rico says it's too bad Melson wasn't named Hare...

The two officials became the highest-profile political casualties yet in the fallout from a disputed effort to take down a weapons-smuggling ring based in Arizona and linked to Mexican drug cartels.

Run by the bureau’s Phoenix division, the operation, called Operation Fast and Furious, ran from late 2009 to early 2011. Its strategy was to watch suspected “straw” gun buyers, rather than moving as quickly as possible to arrest them and seize the weapons, in the hope of identifying higher-level conspirators, as drug investigations are often conducted.

The operation was internally controversial because the firearms bureau traditionally puts a priority on getting guns off the street. It also lacked adequate controls; one straw purchaser bought more than six hundred weapons, and agents lost track of hundreds. Many later turned up at crime scenes in Mexico, and two were recovered at a site in Arizona where a United States Border Patrol agent was killed.

After that killing, bureau agents opposed to the operation reached out to Congress, and two Republican lawmakers— Representative Darrell Issa of California, chairman of the House Oversight Committee, and Senator Charles E. Grassley of Iowa— began an investigation. On Tuesday, they vowed to press on. “Today’s announcement is an admission by the Obama administration that serious mistakes were made in Operation Fast and Furious,” Grassley said, “and is a step in the right direction, that they are continuing to limit any further damage that people involved in this disastrous strategy can do. We’re looking for a full accounting from the Justice Department as to who knew what and when, so we can be sure that this ill-advised strategy never happens again."

Democrats have been largely muted in response to the investigation. Holder also asked the Justice Department’s inspector general to examine the operation. And Democratic lawmakers have joined in criticizing its tactics, while objecting only to Republicans’ efforts to blame senior Obama administration officials for them.

Such accusations have been repeatedly contradicted by testimony from Justice Department and ATF supervisors, including Melson and Burke, that there was no policy directive from Washington or the administration to adopt such an investigative strategy. The two men have also said that they had not known the details of the operation’s tactics, let alone briefed their own superiors about them.

Issa repeated his claims on Tuesday, saying that his committee “will continue its investigation to ensure that blame isn’t offloaded on just a few individuals for a matter that involved much higher levels of the Justice Department.”

Holder did not directly address the operation in his statement thanking Burke, but he referred indirectly to the management distractions, commending “his decision to place the interests of the U.S. Attorney’s Office above all else.” Holder also named B. Todd Jones, the United States attorney for Minnesota, as the new acting director for the firearms bureau, a beleaguered agency that has long been hobbled by gun-rights politics. Five years ago Congress required that the agency’s director be approved by the Senate, but no nominee has since been confirmed. Jones, who also is the chairman of Holder’s advisory committee of prosecutors, will remain a United States attorney.

“I know it’s been a challenging time for this agency, and for many of you,” Jones wrote in an email to the firearms bureau. “As we move forward, we face a more important challenge than what’s been going on outside of ATF these last several months: what’s going on inside ATF.”

Other officials associated with the star-crossed operation have also been swept away in recent weeks. Two ATF Phoenix division supervisors, William Newell and William McMahon, received lateral transfers to positions in Washington. Emory Hurley, an assistant United States attorney in Phoenix who worked on the operation, was transferred to the office’s civil division from its criminal division.

Melson is taking a low-profile position as a “senior advise” for forensic science issues at the Office of Legal Policy in the Justice Department. By contrast, Burke— who was considered a rising Democratic star in a state run by Republicans— is returning to private life. Burke did not return calls on Tuesday. But, in newly released excerpts of his private testimony to Congressional investigators this month, he took responsibility for the operation even as he said he had not known about its tactics. “I get to stand up when we have a great case to announce and take all the credit for it, regardless of how much work I did on it,” he said. “So when our office makes mistakes, I need to take responsibility, and this is a case, as reflected by the work of this investigation, it should not have been done the way it was done, and I want to take responsibility for that, and I’m not falling on a sword or trying to cover for anyone else.”

History for the day

On 31 August 1997, Princess Diana died in a car crash in Paris at the age of 36.

Earthquake update

President Obama has confirmed that the earthquake that occurred in Virginia, roughly ninety miles south of Washington, D.C., was on a previously unknown faultline called Bush's Fault. However, several well-known

conservatives have said the quake was actually caused by our Founding Fathers rolling over in their graves..

Rico says he'll leave the identity of his conservative friend who sent this a secret...

Rico says he'll leave the identity of his conservative friend who sent this a secret...

30 August 2011

Rico does, too

Heather Anderson, a veteran of the credit union industry, a marketing and business development consultant, and the coauthor of Stealing Homes: How to Survive a Foreclosure and Move On With Your Life, has an article in the Los Angeles Times about living only with cash:

I should have known better. I worked in the credit union industry and spent nearly twenty years educating members about risky mortgages, home equity loans, and the importance of thrift. Even so, in 2006, I joined the vanguard of the foreclosed-upon.Rico says he's learned to function without credit since he had to declare bankruptcy after his time in the hospital, and it works fine. (A little more income wouldn't hurt, but it wouldn't change the basic premise.)

It wasn't the bad loan that did us in; although we did stupidly finance one hundred percent of our home's inflated purchase price with an interest-only first mortgage and a home equity loan. At first, I insisted we apply for a traditional, thirty-year fixed mortgage. But, even with his six-figure salary and my good credit, we couldn't qualify in California's high-stakes housing game. I wanted to wait and save up for a down payment, but he needed the tax break. And I'll admit I did want to own a home. He didn't have to twist my arm very hard.

Could we have paid the principal, once the interest-only period ended? Could we have outlasted the recession, and eventually built up some equity? Possibly, but we'll never know. We split up before that could happen.

Death, disease, divorce, and unemployment: these are the ways people lost their homes in the "good ol' days", and that's what happened to me. We hadn't even been in the home one year when we split, and by then the market had already begun its long downhill slide. Despite our home being on a ridge at the end of a cul-de-sac in beautiful San Diego, nobody wanted to buy it, even in a short sale.

The stress of living with an ex took its toll quickly, so I moved out into a rental. My ex moved out too, leaving without providing the bank with his forwarding address. I tried to settle my half of the responsibility, but without any assets to bargain with or any wealthy relatives willing to help, I had little to offer, and the bank foreclosed.

So, just as the subprime mortgage bubble blew up, my credit score did too. I had already consolidated to one credit card, but once the default hit, my credit union increased the interest rate by fifty percent. Thank God that was my only debt.

I made a vow to live a cash-only life. Like I had a choice. But after I lost one American dream, I discovered another. Deciding to live cash only— okay, being forced to live cash only— was the best thing I've ever done. Seriously.

The first and most rewarding change I made was to turn off cable television. Not only did I find myself with plenty of time to take on new moneymaking projects and hobbies, I lost the urge to consume as a pastime. Before, when I shopped, I'd wandered aimlessly through the aisles, hypnotized by all the choices and practically drooling from the intoxication of consumption. I purchased things I didn't need or even want. Once I switched off the "you need more" advertising message and the "what you have isn't good enough" themes on the lifestyle channels (and without credit cards to act on those impulses), I regained my consumer clarity. I shop for what I need; I want less.

My ex and I used to travel several times a year, staying in nice hotels and enjoying nights out on the town. Since we split, I haven't taken a vacation. But then again, I don't need one. Without the stress of a mortgage, I've lost the urge to "escape".

I still drive my 1998 Jetta, which I purchased new and financed with a loan that took six years to pay and cost me thousands in interest. It looks dated, but it's still in excellent condition. I don't have a car note, my insurance is only fifty dollars a month and, even after the last increase in DMV registration, I still pay less than a hundred dollars a year. Is that worth living without cruise control and a rear window that doesn't roll down? You betcha!

Best of all, without the pressure of a mortgage, I was able to pursue self-employment and parenthood with a new boyfriend, who is also committed to a credit-free lifestyle. These days, I work from home while we split time caring for our four-month old son. Our names aren't on the title of our rental home, but it's clean, cozy, and the cost is reasonable.

Do I want to buy another home again? Well, of course. And someday, when the Jetta finally dies and/or my son outgrows the urge to scatter Goldfish crackers from one end of the car to the other, I'll want a new car too.

But this time, I won't finance either one at one hundred percent. Because I learned the lesson we all should have learned since the bubble burst: credit is useful, but it doesn't equal wealth.

Maybe they'll stay, now

The Los Angeles Times has an article about the space station and the Russians:

Russian officials say they have identified what went wrong with the rocket that failed to reach orbit last week. Now the question is whether the explanation will allay enough fears to keep the International Space Station going. A spokesperson for the Federal Space Agency (Roscosmos) told the Russian news agency Itar-Tass that the failure was caused by the rocket's third-stage engine. "It is a malfunction in the engine's gas generator," he said.Rico says this is a good thing; it'd be a shame to bring them home...

Even if you don't know much about rocket science, the announcement’s potential implications are interesting. Space officials had said that the immediate future of the International Space Station rested on whether the Russians could determine what went wrong with the rocket and then fix it before a November deadline. If not, warned NASA’s space station chief, Mike Suffredini, who also happens to be chairman of the international group that operates the space station, the station might have to be abandoned, at least temporarily.

The rocket, which blew up over Russia's Altai region last week, was carrying supplies, not people, but a very similar rocket is used to take scientists to and from the space station. Nobody, not NASA and not Roscosmos, wants to put an astronaut on what might be a faulty rocket.

"We're focused on keeping the crew safe. Our next focus is on keeping the ISS manned," Suffredini was quoted as saying in various media reports. "Flying safely is much, much more important than anything else I can think about right this instant."

The International Space Station has been continuously staffed for more than a decade, but NASA officials say it's not necessarily the end of the world (or the space station) if it goes astronaut-less for some time. At the news conference, Suffredini told reporters that the space station can be flown without a crew. Still, he stressed that having a crew on board is always preferable, especially because crew members can respond to problems on the space station and attempt to fix them before any major damage is done.

NASA did not respond to the L.A. Times' request for comment as to whether this new revelation by Roscosmos will affect whether the space station remains staffed or not. It’s always possible that such a quick investigation could be unsettling to NASA, if not Congress.

Needle art

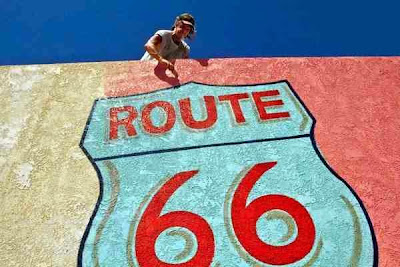

Phil Willon has an article in the Los Angeles Times about one hell of an art project, in an unlikely place:

Along old Route 66, the once-kitschy Overland Motel is crumbling, vacant lots pock downtown, and, as if this remote desert outpost weren't suffering enough, the last car dealership folded up and left behind a blanket of empty asphalt. Not a pretty picture for travelers who might pull off the highway for a burger or to spend the night. Then, about five months ago, a man with a sun-stained face and paint-crusted fingernails drifted in, and the tiny old railroad town of Needles started looking a little brighter.Rico says there's hopefully another guy like this who wants to do Robersonville, North Carolina, where Rico's mother is trying to spruce up downtown...

The first mural popped up on a bare cinder-block wall at the Wagon Wheel Restaurant: a giant Santa Fe locomotive chugging by a roadside sign for the Route 66 Original Diner. Another appeared at the Valero gas station, with two space aliens that look like ET driving down Route 66 in a 1950s Buick. Elvis and Marilyn took over the side wall of the Econo Smog with their two-tone Ford Fairlane convertible parked at the Colorado River; Marilyn sported aviators and the King, white leathers.

All pay homage to Route 66, the Mother Road, which ran from Chicago to Los Angeles, right through the heart of Needles, before it was retired from the federal highway system in 1985. Other larger-than-life odes appeared seemingly overnight at the Needles Point Pharmacy and Liquor Store, Deco Food Service, the local Chevron station, the Miranda Car Wash, and the local Best Western— more than a dozen murals in just a few months, with more in the works.

The man behind the brush, Dan Louden, spent thirty years bouncing around truck stops in the West, hand-painting any long-hauler's piece de resistance on the cabs or trailers. He painted Harleys for the Hell's Angels in San Bernardino until that got a little too dicey for him and hand-lettered signs for fish markets, high schools, and auto parts stores all the way up to Seattle. He's pinstriped more hot rods than he can remember.

"I do it because there's a lot of fringe benefits that come with this. You travel, you do what you want," said Louden, 52, who grew up in Diamond Bar. "I just love the desert. I don't like living in big cities. I don't like the traffic. Out here you can sleep with the door unlocked."

Susan Alexis, owner of the Wagon Wheel, said that, a couple of years back, Louden did odd jobs for her and others around town, but they didn't know he was a master with a few cans of paint.

When he mentioned it to her while breezing through town earlier this year, she hired him on the spot. Alexis had wanted to paint the restaurant's side wall ever since noticing how ugly the bank of cinder blocks looked on Google Maps' Street View. "I just wanted to bring some nostalgia to the building. We have so much history here, but our town doesn't reflect it," Alexis said. "Now, everyone around town is talking about the guy."

Louden said he's been drawing and painting ever since he was a kid but never pursued it. Then one day, when he was about twenty, he delivered paint to an "old school" sign shop in Yucaipa and his life changed forever. Louden has a house outside of Kingman, Arizona that he shares with his girlfriend, Vicky Bowden, a former nurse from Lone Pine.

With work pouring in, they have camped out at the Needles Inn for weeks at a time, working almost every day. It help that he's affordable— $500 for a mural covering the side of a small building— and fast. Most jobs are wrapped up in a day. When they overheat in the scorching Mojave sun, they take a dip in the Colorado.

"It's certainly brightened up downtown, and hopefully it'll help bring more tourists in," said Needles Mayor Edward Paget. "It's not like this was planned. People are doing it on their own and they're being greatly encouraged by both myself and the City Council to improve downtown."

Most of the businesses hiring Louden have stuck to a Route 66 theme, honoring the highway that lit up Needles during its last heyday. In November, the town also is celebrating the 85th anniversary of the road. Needles earned a certain fame when it was named in John Steinbeck's The Grapes of Wrath.

"It was outrageously reasonable, and I think he captured the feel of the small town," said Needles accountant Michael Burger, who hired Louden to liven up his office building earlier this month. "It's a nice thing he's doing for the town." Burger had a snapshot of his restored '57 Chevy truck and handed it to Louden, telling him to use that and then "do whatever you want". Twelve hours later, his building was covered with the gang from the Peanuts comic, including Snoopy's brother Spike from Needles, one of the town's biggest celebrities. Charlie Brown is at the wheel of the truck.

Louden also was hired to paint a memorial inside the San Bernardino County Sheriff's Station in Needles honoring Deputy Russell Dean Roberts, who was killed in 1995 while investigating an accident in the town.

Captain Marty Brown of the county fire department also wants to hire Louden to paint the station in Needles. "We just need to give the front a facelift, maybe to look like an old-school fire station," Brown said. "The firefighters will probably have to pay for it out of pocket, since it's pretty unlikely we're going to pay for that with public funds."

Louden says times are tough for everyone these days, which is why he keeps his prices low. He can afford to, he said, because there's more work than he can handle. "The first sign painter I ever ran into told me that if you learn how to do this, you'll never go hungry. And he's absolutely right," Louden said. "You'll always find someone who needs something done."

Don't know when to lie down and die

Reuters has an article about HP resurrecting (probably the right word) the TouchPad:

Hewlett-Packard plans to crank out "one last run" of TouchPads, days after declaring it will kill off a line of tablets that failed to challenge Apple's command of the booming market.Rico says a 'personal devices division' ought to be making vibrators, not computers. But 'losing money on every TouchPad'? That's like the old joke about only losing a buck on each piece, but making it up on the volume...

A day after the chief of HP's personal devices division told Reuters that the TouchPad might get a second lease on life, HP announced a temporary about-face on the gadget after being "pleasantly surprised" by the outsized demand generated by a weekend fire-sale. HP slashed the price of its tablet to $99 from $399 and $499 the weekend after announcing the TouchPad's demise on 18 August, part of a raft of decisions intended to move HP away from the consumer and focus on enterprise clientele.

That ignited an online frenzy and long lines at retailers as bargain-hunters chased down a gadget that had been on store shelves just six weeks. "The speed at which it disappeared from inventory has been stunning," the company said. "We have decided to produce one last run of TouchPads to meet unfulfilled demand."

HP may lose money on every TouchPad in its final production run. According to IHS iSuppli's preliminary estimates, the 32GB version carries a bill of materials of $318. "We don't know exactly when these units will be available or how many we'll get, and we can't promise we'll have enough for everyone. We do know that it will be at least a few weeks before you can purchase," HP said in a blogpost.

Critics have blasted HP for wavering on pivotal decisions, such as its original stated intention to integrate its webOS software into every device it makes, followed by a decision to stop making webOS gadgets, including the TouchPad. The storied Silicon Valley giant is struggling to shore up margins as smartphones and tablets eat away at its core PC business, the world's largest. On 18 August, HP said it was also considering spinning off the PC division.

CEO Leo Apotheker is under immense pressure from investors unhappy with HP's back-and-forth on strategy. The former SAP chief has also been forced to slash HP's sales estimates three times since he took over last November. In a resounding rejection of his grand vision, shareholders sent HP shares down almost twenty percent the day it announced its sweeping moves, which included a pricey acquisition of software player Autonomy. That wiped out sixteen billion dollars of value from HP, in the stock's worst single-day fall since the Black Monday stock market crash in October of 1987.

HP declined to comment beyond the blogpost. Shares in the company were down marginally in after-hours trading on Tuesday.

Finding the bad guys

Nicholas Wade has an article in The New York Times about the bubonic plague:

Beneath the Royal Mint Court, diagonally across the street from the Tower of London, lie 1,800 mute witnesses to the foresight of the city fathers in the year 1348. Recognizing that the Black Death then scourging Europe would inevitably reach London, the authorities prepared a special cemetery in East Smithfield, outside the city walls, to receive the bodies of the stricken.Rico says they're ignoring certain facts about medieval life: people had fleas, and were in poor health generally. Once you got sick, you were easily dead...

By autumn, the plague arrived. Within two years, a third or so of London’s citizens had died, a proportion similar to that elsewhere in Europe. The East Smithfield cemetery held 2,400 of the victims, whose bodies were stacked five deep.

The agent of the Black Death is assumed to be Yersinia pestis, the microbe that causes bubonic plague today. But the epidemiology was strikingly different from that of modern outbreaks. Modern plague is carried by fleas and spreads no faster than the rats that carry them can travel. The Black Death seems to have spread directly from one person to another.

Victims sometimes emitted a deathly stench, which is not true of plague victims today. And the Black Death felled at least thirty percent of those it inflicted, whereas a modern plague in India that struck Bombay in 1904, before the advent of antibiotics, killed only three percent of its victims.

These differences, as well as the fear that the Black Death might re-emerge, have prompted several attempts to retrieve DNA from Black Death cemeteries. The latest of these attempts is reported in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences by a team led by Hendrik N. Poinar of McMaster University in Ontario, Canada and Johannes Krause of the University of Tübingen in Germany.

They looked for surviving fragments of DNA in bones and teeth that archaeologists had excavated from the East Smithfield site in the 1980s. The DNA matched that of the modern-day microbe, confirming, as have several other studies, that Yersinia pestis was indeed the agent of the Black Death. Sharon DeWitte, a member of Dr. Poinar’s team, was one of several skeptics who had doubted the microbe’s role. “I’m very happy to find out I was wrong,” said Dr. DeWitte, a paleodemographer at the University of South Carolina. “In science, if you’re open to alternative possibilities, you can change your mind.”

Dr. Poinar’s team also looked for the microbe’s DNA in another medieval London cemetery, that of St. Nicholas Shambles, which was closed before the Black Death struck. They found no sign of it there, indicating that Yersinia pestis was not already present in the English population before the Black Death, so it must have arrived from elsewhere.

If Yersinia pestis was indeed the cause of the Black Death, why were the microbe’s effects so different in medieval times? Its DNA sequence may hold the answer. Dr. Poinar’s team has managed to reconstruct a part of the microbe’s genetic endowment. Yersinia pestis has but a single chromosome, containing the bulk of its genes, and three small circles of DNA known as plasmids.

The team has determined the full DNA sequence of the plasmid known as pPCP1 from the East Smithfield cemetery. But, disappointingly, it turns out to be identical to the modern-day plasmid, so it explains none of the differences in the microbe’s effects.

“It was probably a naïve approach to assume we’d get the smoking gun on first attempt,” Dr. Poinar said.

Mark Achtman, an expert on plague who works at University College Cork in Ireland, said that the new study was “technologically interesting” but that a great deal more of the microbe’s DNA needed to be sequenced to obtain scientifically important results.

This is indeed Dr. Poinar’s plan. The challenge in reconstructing the microbe’s DNA from the East Smithfield cemetery is that it is highly fragmented. The Yersinia pestis chromosome is 4,653,728 units of DNA in length, but the bits of DNA from the cemetery are no more than fifty to sixty units long.

Determining the order of the chemical units in such fragments has become possible only in the last few years with the development of new DNA sequencing machines that work with short fragments.

Another technical challenge is to separate the plague DNA from that of the human and other microbial DNA in the ancient bones. One technique that Dr. Poinar’s team has used is to tether plasmid DNA from the modern plague microbe to plastic beads. DNA is quick to bind to strands of DNA of the complementary sequence, as in the DNA double helix. So the beads act as fishing rods to pull out the DNA of interest.

“It’s probably exceptionally important to find out what made this bug so deadly in the past,” Dr. Poinar said.

Dignity, even in death, apparently

David Kirkpatrick has an article in The New York Times about the losing side in Libya:

Faraj Mohamed cast his eyes across the hospital room with the furtive anxiety Tripoli residents used to display when they spoke ill of Colonel Muammar el-Qaddafi. “I myself would die a thousand times for Qaddafi, even now,” said Mohamed, a twenty-year-old soldier, lying in a hospital as a prisoner of the rebels who ousted the Libyan leader. “I love him because he gave us dignity, and he is a symbol for the patriotism of the country.”Rico says that's devotion, however deluded, for you; some Nazis probably said the same things in 1945. But, in an ugly civil war, the rebels would rape the men and kill the women...

A week after rebels breached Colonel Qaddafi’s stronghold in Tripoli, Mohamed offered a bracing reminder of the obstacles confronting the new provisional government still taking shape. Surt, Mohamed’s hometown as well as Colonel Qaddafi’s, remains under the control of forces loyal to the ousted Libyan leader, as do Sabha in the south and Bani Walid in the central west.

At moments when his guards were out of earshot, Mohamed expressed the special combination of allegiance to Colonel Qaddafi and the fear of chaos without him that still inspired fighters to rally around his lost cause, even after his authority had collapsed.

As Mohamed spoke of defending the Libyan leader, Colonel Qaddafi had vanished into hiding, while his wife Safiya, daughter Aisha, and sons Mohammed and Hannibal fled to Algeria. The spouses of Colonel Qaddafi’s children and their offspring arrived there as well.

But Mohamed said he fought on, fearful of a future without Colonel Qaddafi. “This war will happen again, and Libya will experience the same thing that is happening in Egypt,” Mohamed warned, repeating the series of imagined woes that Colonel Qaddafi’s supporters said had followed the ouster of that country’s strongman, Hosni Mubarak: “Murder and killing and stealing and chaos.”

“What is happening now is because of the rebels, not Qaddafi,” Mohamed said, his leg in a cast and a wound on his back. He lay with five other captives in a prison unit of the Mitiga air base hospital, with an armed guard in the hall. Libya’s provisional government calls them prisoners of war, but Mohamed was the only one who admitted to fighting for Colonel Qaddafi. Two fellow patients said they were migrant workers, from Niger and Somalia, who had been falsely accused of being mercenaries. Another patient, a Libyan, said he had simply been shot in the street. “I am innocent,” he said. Another was handcuffed to his bedrail. All said they were well treated. During recent visits, hospital staff members brought them special meals just before sunset to break the daylong Ramadan fast, though the seriously sick are not typically expected to keep the fast.

When the rebel captors entered, Mohamed often abruptly switched the tone of his comments. “Now I think that all Libya is more united,” he volunteered at one point, temporarily contradicting his previous statements for the benefit of his captors. In another apparent attempt to mollify his captors, he at times blamed Colonel Qaddafi’s propaganda for his plight. Until he was captured, he said, he had believed the reports on state- run television that the rebels were foreigners, bearded Islamic radicals, or bloodthirsty monsters who ripped out the hearts of Qaddafi loyalists.

“I didn’t watch al-Jazeera or al-Arabiya,” he maintained, referring to the two pan-Arab satellite news networks. “I didn’t know the rebels were Libyans.” Equally uncertain was his claim that in his four months of service, he had not harmed or killed anyone.

But other comments echoed more widespread sentiments among those who support the Brother Leader, as Colonel Qaddafi liked to be called. Many remember that, when Colonel Qaddafi took power in 1969, Libya was a poor and almost entirely undeveloped nation of Bedouin herders whose oil wealth appeared to enrich mainly the foreign companies that exploited it. Riding the tide of soaring oil prices over the following decades, he pursued development programs that— though hobbled by corruption and inefficiency— helped turn Libya into a primarily urban country.

Its citizens lacked basic freedoms, but thanks to oil wealth, they believed they enjoyed a relatively higher standard of living than their regional neighbors.

Mohamed, a sixth-grade dropout and son of a doorman, said Colonel Qaddafi had brought Libyans self-respect by kicking out foreign colonialists; under Colonel Qaddafi, Libyans celebrated a national holiday every year on the day the United States evacuated the air base that included the hospital where Mohamed was held. Then there was the special patronage— buildings, roads, schools, hospitals, and jobs— lavished on Colonel Qaddafi’s two former hometowns, Surt and Sabha. Surt flourished as Colonel Qaddafi’s favorite place to hold conferences, Mohamed said of the Mediterranean port city that is his hometown as well. “Surt really loves Qaddafi,” he said. “And they will fight for him.”

But he also professed a high-minded fear that, without Colonel Qaddafi’s strong hand to preserve order, the rebels would drag Libya into chaos, a faint echo of the justification used by many Middle Eastern dictators who portray their iron-fisted rule as a bulwark against lawlessness.

In a Tripoli neighborhood supportive of Colonel Qaddafi, Mohamed recalled, he met residents who “said they were scared the rebels would rape the women and kill the men”. Residents of some loyalist neighborhoods fought for the colonel even after rebels were inside his compound.

Having worked a series of low-paying odd jobs since childhood, Mohamed said, he was drawn to the promise of a soldier’s training and paycheck as well. He said he had seen a television commercial promising a good salary and training for young men who enlisted in Colonel Qaddafi’s defense. So he signed up. He was shipped to Tripoli with barely a lesson on cleaning his Kalashnikov. Mohamed said he was housed in a large barracks and provided insufficient food and water, so he and his fellow soldiers turned to their neighbors for handouts.

Even so, he stayed loyal, he said. Other soldiers shed their uniforms and quietly slipped away after Colonel Qaddafi’s compound fell. But Mohamed fought on until the next day, when his militia was in a battle. His comrades turned to flee and so did Mohamed, he said, until rebels shot him in the foot. “For God’s sake, don’t kill me!” he said he pleaded. A moment after recalling that scene, though, his quixotic courage returned. “I would sacrifice myself, I would sacrifice my family,” he said. “I would sell myself for Qaddafi.”

Going too far

Rico says you gotta go a long way against religion to be too far for him, but James Dao has an article in The New York Times about people doing just that in Houston:

Every week, thousands of veterans are buried at national cemeteries, often to the baleful sound of a bugle. Yet even for families that quietly mourn their dead, these can be the most public of private affairs, taking on deep meaning— about politics, war,and religion — to others, particularly other veterans.Rico says the families that want them will surely ask...

So in Houston, with one of the nation’s busiest national cemeteries, controversy exploded when the new cemetery director began enforcing a little-noticed 2007 policy that prohibits volunteer honor guards from reading recitations, including religious ones, in their funeral rituals, unless families specifically request them. The new enforcement outraged members of local veterans organizations, who have long infused their ceremonies with references to God. This summer, they filed a lawsuit against the Department of Veterans Affairs that has turned the national cemetery into a battleground over the role of prayer in veterans’ burials.

The plaintiffs, aided by a conservative legal group, the Liberty Institute, contend they should be allowed to use a Veterans of Foreign Wars script dating from World War One that refers to the deceased as “a brave man” with an “abiding faith in God” and that seeks comfort from an “almighty and merciful God”. The Institute has broadcast the dispute nationwide, with slick videos and a website declaring that “Jesus is not welcome at gravesides”. “In all these years, we’ve not had one complaint,” said Inge Conley, a retired Army master sergeant who is commander of the Veterans of Foreign Wars, District 4, one of the plaintiffs.

The lawsuit, which alleges religious discrimination by the government, and videos have generated angry letters and internet commentary against the Department of Veterans Affairs, as well as demands from members of the Texas Congressional delegation, mostly Republicans, that the Obama administration fire the Houston cemetery director, Arleen Ocasio.

Department of Veterans Affairs officials say that the original policy, enacted under President George W. Bush, resulted from complaints about religious words or icons being inserted unrequested into veterans’ funerals. They noted that active duty military honor guards, including the teams that do funerals at Arlington National Cemetery, say almost nothing during their ceremonies. “We do what the families wish,” said Steve L. Muro, the under secretary for memorial affairs. “I always tell my employees we have just one chance to get it right.”

Though two of the largest veterans organizations, the American Legion and Veterans of Foreign Wars, have criticized the Houston National Cemetery, some veterans’ advocates have risen to the department’s support. Those advocates say that families who want prayers can have them, and assert that the Liberty Institute has blown the dispute out of proportion in order to embarrass the Obama administration. Lawyers with the Liberty Institute deny that.

Jim Strickland, a Vietnam-era veteran who runs a blog called VAWatchdogtoday.org, said that he had not heard of similar problems at other national cemeteries, and that the fight in Houston boiled down to a local power struggle over funeral rituals. “The message was that the people in Houston should not do this VFW ritual uninvited, and they did not want to hear that,” Strickland said.

The Department of Veterans Affairs buries 110,000 people— most of them veterans, but some family members— each year in the 131 national cemeteries it oversees. To be eligible for burial in one of those cemeteries, a veteran cannot have received a dishonorable discharge, or been convicted of treason or a capital crime. At a family’s request, the Defense Department is required to send uniformed service members to a veteran’s funeral, usually two. But many families ask local veterans organizations to send volunteer honor guard teams, which are larger and can perform more elaborate rituals that may include special recitations and the playing of taps on real bugles. For that reason, come rain or shine, blistering heat or bone-numbing cold, honor guards— usually graying World War Two, Korean, and Vietnam veterans— arrive at national cemeteries almost every day, steady as postmen. Dressed in faded military uniforms or somber suits, black berets or VFW caps, they shoulder rifles and tuck old-fashioned bugles under their arms before each ceremony. George J. Weiss Jr., who served with the Marine Corps in World War Two, formed a volunteer rifle squad in Minnesota thirty years ago when the family of a deceased friend could not find an honor guard to perform at his funeral. What started with six people has grown into a squad of 130 volunteers who attend services every day at Fort Snelling in Minneapolis, forty miles from Weiss’ home. Since starting the squad, Weiss, a former Ford assembly plant worker, has attended funerals almost every Friday, he said, missing only a handful because of driving snowstorms. “We enjoy the camaraderie,” he said in a telephone interview. “It’s a closed club. There’s not that many people that can join us.” Weiss said that, unlike the Houston team, his squad says almost nothing during its ritual, except to express gratitude to the family upon presenting it with a flag. “We try to make it as fast and as dignified as possible,” he said. In Houston, Felix J. Sivcoski, 84, has been the chaplain for the local VFW honor guard for seven years. He says that he modifies his script at the request of families, but that people who request the VFW ritual generally understand that it includes a prayer. “I’m helping my deceased veterans be buried with dignity,” said Sivcoski, a retired oil field worker who served in the Navy during World War Two. Plaintiffs in the lawsuit include the American Legion and a group called the National Memorial Ladies, which says it has been barred from giving crosses or condolence cards with religious greetings to veterans’ families without prior consent. The disputed 2007 directive says that “the deceased’s survivor(s), and only they, will identify the text to be read” at services in national cemeteries. The plaintiffs assert that Ocasio has interpreted that passage to mean that the veteran’s groups cannot discuss their ritual with veterans’ families. If families do not specifically ask for religious prayers, none are allowed, they say. “If the government would just go away and get out of it, everything would be fine,” said Hiram Sasser, director of litigation for the Liberty Institute. The Department of Veterans Affairs said that funeral directors, rather than the veterans themselves, should tell families the details of the VFW or other rituals, to give those families room to make their own decisions on what is recited. “If the family wants prayers, the family will get them,” said John R. Gingrich, the department’s chief of staff.

Cruel joke

Ben Johnson and Josh Voorhees have an article in The Slate about a poor woman who tangled with Hurricane Irene and lost:

The death toll from Irene now stands at forty, with the latest confirmed casualties including an 82-year-old Holocaust survivor, who drowned in a Catskill cottage during the storm. New York police say that Rozalia Stern-Gluck of Brooklyn had been vacationing with family and friends in Fleischmanns, New York, where she was trapped in her cottage when a nearby creek overflowed on Sunday. More than six feet of water filled the woman’s cottage, officials said. The New York Daily News reports that Stern-Gluck originally hailed from Russia and that she was a Holocaust survivor. “She survived Hitler, but she couldn’t survive Irene,” Isaac Abraham, a Hasidic community leader from Brooklyn, told the paper.

Rico says this is a cruel joke, even for the karma lords...

Oops is now an ATF term

Sharyl Attkisson has an article at CBSNews.com about the director of the BATFE:

Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives acting director Kenneth Melson is being moved out of the top job at the bureau, ATF special agents in charge announced during an internal conference call today. He will transfer to the Justice Department and assume the position of senior advisor on forensic science in the Office of Legal Programs.Rico says it's amazing that, no matter how screwed up their operations, no one actually got fired...

The DOJ announced that Melson will be replaced by Todd Jones, the U.S. Attorney for Minnesota. "As a seasoned prosecutor and former military judge advocate, Jones is a demonstrated leader who brings a wealth of experience to this position," said Attorney General Eric Holder.

Also, Dennis Burke, the U.S. Attorney for Arizona, has submitted his resignation to President Obama, effective immediately. In an email sent to his staff Tuesday, Burke says his long tenure in public office has been intensely gratifying and intensely demanding. Burke was interviewed by Congressional investigators behind closed doors on 18 August.

Sources tell CBS News that the Assistant U.S. Attorney in Phoenix, Emory Hurley, who worked under Burke and helped oversee the controversial case, is also expected to be transferred out of the Criminal Division into the Civil Division. Justice Department officials provided no immediate comment or confirmation of that move. The flurry of personnel shifts come as the Inspector General continues investigating the so-called Gunwalker scandal at the Justice Department and the ATF.

The 'gunwalking' scandal centered on an ATF program that allowed thousands of high-caliber weapons to knowingly be sold to so-called "straw buyers" who are suspected as middlemen for criminals. Those weapons, according to the Justice Department, have been tied to at least twelve violent crimes in the United States, and an unknown number of violent crimes in Mexico. Dubbed Operation Fast and Furious, the plan was designed to gather intelligence on gun sales, but ATF agents have told CBS News and members of Congress that they were routinely ordered to back off and allow weapons to "walk" when sold. Previously, the ATF Special Agent in Charge in Phoenix, Bill Newell, was reassigned to headquarters, and two Assistant Special Agents in Charge under Fast and Furious, George Gillett and Jim Needles, were also moved to other positions.

Russian aerospace? Why not? It can only crash once

Rico says that Andrew Kramer has an article in The New York Times about the latest airliner, out of the Sukhoi plant:

Airlines are a cautious lot, slow to trust a new airplane maker with multibillion-dollar orders and passenger lives. It took Embraer, a Brazilian maker of regional jets, two decades to become a major supplier to the industry. So Sukhoi, a Russian company best known for making supersonic fighter jets, did not exactly get off to an auspicious start. When it delivered one of the first of its highly promoted new hundred-seat Superjets to Aeroflot in June, a piece of safety equipment immediately broke down, prompting Sukhoi to ground the plane.Rico says that the Sukhoi website is claiming a third one's been sold, but the United Aircraft Corporation in Russia is not the same as the United Aircraft corporation (now United Technologies) in the States, for whom Rico's father used to work (in their missile division)...

Although the plane was fixed and is flying again, the lapse shows just how difficult a path Sukhoi faces to persuade Western airlines to buy airplanes from a Russian state company. Russia’s aviation industry has long been plagued by safety problems, breakdowns and lethal crashes, rendering it virtually unable to sell planes outside the former Soviet Union, Iran, Cuba, and parts of Africa.

“Historically, Russian aircraft have an image that will take a long time to address,” Les Weal, an analyst at Ascend, an aviation consultancy in London that advises the insurance industry on safety, said in a telephone interview. “Sukhoi may be excited about their airplane,” he said. “But I’m not sure that will translate into a lot of orders from mainstream airlines. It would take a huge leap of faith for an airline to turn to a newcomer.”

But Sukhoi has high expectations for the Superjet 100, the first wholly new Russian civilian aircraft design since the breakup of the Soviet Union. The list price for the chubby, single-aisle aircraft is $31.7 million, about one-third cheaper than comparable short-hop jets from Embraer or Bombardier of Canada, Sukhoi says.

Gone is the grim upholstery and fluorescent lighting of the cramped, even scary, interiors of the Tupolev series of jets that are still operated by domestic Russian carriers. The Superjet’s cabin feels roomy, the overhead luggage bins can hold standard carry-on luggage and the lighting is soft. The high-bypass engines, a novelty for Russian passenger planes, hum rather than scream at take-off.

Sukhoi, which is in talks to sell the planes to the American carriers Delta and SkyWest as well as to other Western airlines, hopes to sell eight hundred Superjets over the next twenty years. Besides two planes delivered to Aeroflot, Sukhoi has provided one to the Armenian national airline, Armavia. It has also agreed to provide fifteen to Mexico’s second-largest airline, Interjet, and Sukhoi has 176 Superjet orders in total.

Rather than emphasize the plane’s Siberian origins, with whatever associations with hardship or disaster that may evoke, Sukhoi has marketed it by pointing to its French and Italian partners, which worked in joint ventures to design the engines and provide the avionics. “Yes, it is a Russian aircraft,” Olga Kayukova, a spokeswoman for Sukhoi’s parent company, United Aircraft Corporation, said in an interview. However, “it is made in cooperation with world-leading suppliers".

Stephen McNamara, a spokesman for Ryanair, the low-cost Irish carrier, said his company would have no qualms about looking at a Russian plane so long as it met European Union safety standards. Most passengers, he said, don’t care what type of airplane they fly. “They know the airline, but not the airplane,” he said. Ryanair has talked to Sukhoi about its new plane, he said, and the budget airline was more concerned that the plane was too small for its routes than about the reputation of Russian airplanes.

On the Superjet delivered to Aeroflot, a meter to detect leaks in the pipes that funnel fresh air, called bleed air, into the cabin had malfunctioned. The company said passengers were never at risk, as the actual air supply was not affected. Sukhoi found a silver lining in the incident, by explaining it had grounded the plane from an abundance of caution that in fact illustrated its new safety culture. The Superjet was the first Russian airplane with such a detector, which is standard on Western planes. The planes also weigh two tons more than initial estimates presented to airlines, hurting fuel economy and making them less attractive. Sukhoi has said such deviations are typical for new aircraft.

Russian jets have had a rough spell recently, making the sales pitch even more difficult. In 2006, about four hundred people died in Tupolev jet crashes in Russia and the Ukraine. This June, a Tu-134 crashed while approaching a provincial airfield, killing most of the 52 people on board. (Tupolevs are made by another division of United Aircraft Corporation.) International experts blamed the age of the planes for the accidents, but said cavalier attitudes about safety that pervade Russian industry also contributed. A year ago, for example, the Russian television station NTV reported that seventy engineers at the plant making the Superjet had obtained fake engineering diplomas by bribing a local technical college; Sukhoi said those employees were not directly involved in assembling the planes.

Despite the high barrier to entry internationally for new passenger jets, Kayukova said airlines were eager for alternatives to Embraer and Bombardier for regional jets and were searching for a third supplier for midrange jets like the Boeing 737 and Airbus A320.

Ryanair this year announced negotiations to buy a planned Chinese competitor to the Boeing 737, called the C919, which is expected to be cheaper. Kayukova said Russia would surely be able to compete with China on quality, because China is not a traditional aerospace power. As if to emphasize this lineage, the Superjet being promoted at an air show in Moscow this month was named the Yuri Gagarin, after the Russian who was the first man in space.

By the late 1990s, Russia’s civilian aerospace industry had fallen on hard times. It had become clear that the nation’s wide-body and midrange jets had no market outside the former Soviet Union and a few one-time client states. The Ilyushin aircraft company, for example, sold only a dozen of its Il-96 flagship long-haul jets, including one with a convertible passenger or VIP cabin that was sometimes used as the presidential jet for Fidel Castro.

Surrendering some pride, the Russian aviation industry took aim instead at Bombardier and Embraer, and formed joint ventures with Western companies to fill technological gaps. Alenia Aeronautica, a division of the Italian engineering giant Finmeccanica, owns about 25 percent of the Superjet program and is helping to market the plane in Western Europe, North and South America, Japan, and Australia through a subsidiary based in Venice, known as SuperJet International.

Sukhoi consulted with Boeing on after-sales service, and it installed avionics from the French company Thales. The plane is certified to fly in former Soviet countries, and is awaiting certification for the European Union. Sukhoi has said it will apply to the Federal Aviation Administration for certification, but only after it has a firm order from a United States customer. “We will be facing the same problem as Japanese car manufacturers faced at the beginning,” Giacomo Perfetto, head of communications for SuperJet International, said in a telephone interview. “When they see the airplane fly, they will change their minds.”

Them, regardless

Rico says he doesn't usually but, since Elizabeth Potter of Unity Productions Foundation asked nice, he's posting a 'be nice to Muslims' video, oddly enough in memory of 9/11:

They are part of the national fabric that holds our country together. They contribute to America in many ways, and deserve the same respect as any of us.

Worse there, amazingly

Abby Goodnough and Danny Hakim have an article in The New York Times about the impact of Hurricane Irene in, of all places, Vermont:

While most eyes warily watched the shoreline during Hurricane Irene’s grinding ride up the East Coast, it was inland— sometimes hundreds of miles inland— where the most serious damage actually occurred. And the major culprit was not wind, but water.Rico says he'd said 'Nah' when someone mentioned the damage in Vermont the other day; surely, having moved north and lost steam, Irene couldn't have been worse there, but she was, and there are pictures to prove it:

As blue skies and temperate breezes returned on Monday, a clearer picture of the storm’s devastation emerged, with the gravest consequences stemming from river flooding in Vermont and upstate New York. In southern Vermont, normally picturesque towns and villages were digging out from thick mud and piles of debris that Sunday’s floodwaters left behind. With roughly 250 roads and several bridges closed off, many residents remained stranded in their neighborhoods; others could not get to grocery stores, hospitals or work. It was unclear how many people had been displaced, though the Red Cross said more than 300 had stayed in its shelters on Sunday, and it expected the number to grow. In upstate New York, houses were swept from their foundations, and a woman drowned on Sunday when an overflowing creek submerged the cottage where she was vacationing. Flash floods continued to be a concern into Monday afternoon. In the Catskills, where Governor Andrew M. Cuomo led a helicopter tour of suffering towns, cars were submerged, crops ruined, and roads washed out. In tiny, hard-hit Prattsville, what looked like a jumble of homes lay across a roadway, as if they had been tossed like Lego pieces.

“We were very lucky in the city, not quite as lucky on Long Island, but we were lucky on Long Island,” Cuomo said. “But Catskills, mid-Hudson, this is a different story and we paid a terrible price here, and many of these communities are communities that could least afford to pay this kind of price. So the state has its hands full.”

In Vermont, officials recovered the body of a man who was tending the municipal water system in Rutland during the storm. They said his son, who was with him at the time, was also feared dead. A 21-year-old woman died after being swept into the Deerfield River in Wilmington, a small town west of Brattleboro, and a man was found dead in Ludlow. As of Monday afternoon, the storm had caused at least forty deaths in eleven states, according to The Associated Press.

“This is a really tough battle for us,” Governor Peter Shumlin of Vermont said after surveying the damage across the state in a helicopter. “What you see is farms destroyed, crops destroyed, businesses underwater, houses eroded or swept away, and widespread devastation.”

In the Catskills, state and local officials had, by Monday afternoon, carried out 191 rescues since the storm began, often plucking people from cars or homes as water rose. State officials confirmed six people had died in connection with the storm: five drowned and one was electrocuted.