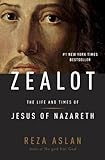

Delancey Place has an excerpt from Reza Aslan's new book, Zealot, about Jerusalem:

In 63 B.C.E., the Romans conquered and occupied the Jewish holy land, and the reaction of the Jewish people was one of escalating defiance, which culminated over 120 years later in the Jewish Revolt of 64-66 of the Common Era, in which they expelled the Romans from their lands. (This defiance is essentially the same as the defiance seen in countries occupied by another nation's armies during modern times). In this cauldron of defiance, many Jews arose claiming to be the Messiah: the one who would rebuild David's kingdom and reestablish the nation of Israel. One of them was Jesus of Nazareth. (In 70 of the Common Era, the Romans returned and destroyed the Temple and the cities of the Holy Land, sending the Jews on a diaspora that did not end until the reestablishment of the state of Israel in the twentieth century):

Rico says religion is a great cover; it allows you to do almost anything in the name of God... (But Rico still fails to understand why a Roman torture device, the crucifix, is the universal symbol for that dead Jewish guy, Jesus. I mean, how many people wear them around their neck without thinking about what it really stands for?)

In 63 B.C.E., the Romans conquered and occupied the Jewish holy land, and the reaction of the Jewish people was one of escalating defiance, which culminated over 120 years later in the Jewish Revolt of 64-66 of the Common Era, in which they expelled the Romans from their lands. (This defiance is essentially the same as the defiance seen in countries occupied by another nation's armies during modern times). In this cauldron of defiance, many Jews arose claiming to be the Messiah: the one who would rebuild David's kingdom and reestablish the nation of Israel. One of them was Jesus of Nazareth. (In 70 of the Common Era, the Romans returned and destroyed the Temple and the cities of the Holy Land, sending the Jews on a diaspora that did not end until the reestablishment of the state of Israel in the twentieth century):

The first century was an era of apocalyptic expectation among the Jews of Palestine, the Roman designation for the vast tract of land encompassing modern-day Israel & Palestine, as well as large parts of Jordan, Syria, and Lebanon. Countless prophets, preachers, and messiahs tramped through the Holy Land, delivering messages of God's imminent judgment. Many of these so-called false messiahs we know by name. A few are even mentioned in the New Testament. The prophet Theudas, according to the book of Acts, had four hundred disciples before Rome captured him and cut off his head. A mysterious charismatic figure known only as 'the Egyptian' raised an army of followers in the desert, nearly all of whom were massacred by Roman troops. In 4 before the Common Era, the year in which most scholars believe Jesus of Nazareth was born, a poor shepherd named Athronges put a diadem on his head and crowned himself 'King of the Jews'; he and his followers were brutally cut down by a legion of soldiers.

Another messianic aspirant, called simply 'the Samaritan,' was crucified by Pontius Pilate, even though he raised no army and in no way challenged Rome, an indication that the authorities, sensing the apocalyptic fever in the air, had become extremely sensitive to any hint of sedition. There was Hezekiah the bandit chief, Simon of Peraea, Judas the Galilean, his grandson Menahem, Simon son of Giora, and Simon son of Kochba, all of whom declared messianic ambitions and all of whom were executed by Rome for doing so. Add to this list the Essene sect, some of whose members lived in seclusion atop the dry plateau of Qumran on the northwestern shore of the Dead Sea; the first-century Jewish revolutionary party known as the Zealots, who helped launch a bloody war against Rome; and the fearsome bandit-assassins whom the Romans dubbed the Sicarii (the Daggermen), and the picture that emerges of first-century Palestine is of an era awash in messianic energy...

Within a few years after the Roman conquest of Jerusalem, an entire crop of landless peasants found themselves stripped of their property with no way to feed themselves or their families. Many of these peasants immigrated to the cities to find work. But, in Galilee, a handful of displaced farmers and landowners exchanged their plows for swords and began fighting back against those they deemed responsible for their woes. From their hiding places in the caves and grottoes of the Galilean countryside, these peasant warriors launched a wave of attacks against the Jewish aristocracy and the agents of the Roman Republic. They roamed through the provinces, gathering to themselves those in distress, those who were dispossessed and mired in debt. Like Jewish Robin Hoods, they robbed the rich and, on occasion, gave to the poor. To the faithful, these peasant gangs were nothing less than the physical embodiment of the anger and suffering of the poor. They were heroes: symbols of righteous zeal against Roman aggression, dispensers of divine justice to the traitorous Jews. The Romans had a different word for them. They called them lestai: bandits.

'Bandit' was the generic term for any rebel or insurrectionist who employed armed violence against Rome or its Jewish collaborators. To the Romans, the word 'bandit' was synonymous with 'thief' or 'rabble-rouser.' But these were no common criminals; the bandits represented the first stirrings of what would become a nationalist resistance movement against the Roman occupation. This may have been a peasant revolt; the bandit gangs hailed from impoverished villages like Emmaus, Beth-horon, and Bethlehem. But it was something else, too. The bandits claimed to be agents of God's retribution. They cloaked their leaders in the emblems of biblical kings and heroes and presented their actions as a prelude for the restoration of God's kingdom on earth. The bandits tapped into the widespread apocalyptic expectation that had gripped the Jews of Palestine in the wake of the Roman invasion. One of the most fearsome of all the bandits, the charismatic bandit chief Hezekiah, openly declared himself to be the Messiah, the promised one who would restore the Jews to glory.

Messiah means 'anointed one'.The title alludes to the practice of pouring or smearing oil on someone charged with divine office: a king, like Saul, or David, or Solomon; a priest, like Aaron and his sons, who were consecrated to do God's work; a prophet, like Isaiah or Elisha, who bore a special relationship with God, an intimacy that comes with being designated God's representative on earth. The principal task of the Messiah, who was popularly believed to be the descendant of King David, was to rebuild David's kingdom and reestablish the nation of Israel. Thus, to call oneself the Messiah at the time of the Roman occupation was tantamount to declaring war on Rome. Indeed, the day would come when these angry bands of peasant gangs would form the backbone of an apocalyptic army of zealous revolutionaries that would force the Romans to flee Jerusalem in humiliation."

Rico says religion is a great cover; it allows you to do almost anything in the name of God... (But Rico still fails to understand why a Roman torture device, the crucifix, is the universal symbol for that dead Jewish guy, Jesus. I mean, how many people wear them around their neck without thinking about what it really stands for?)

No comments:

Post a Comment

No more Anonymous comments, sorry.